The general perception that there aren’t any women producers in electronic music is the first of the myths that I take to task in my forthcoming book. I’m sharing key ideas from each chapter as content on Instagram and in longer form here. This particular myth is very well fed and fattened up by the fact that we can’t see women and gender expansive producers in very many places, so people can rarely name any besides the few big superstars that dominate the top slots in charts, music sales and headline slots at events. And that doesn’t just apply to men, it’s everyone.

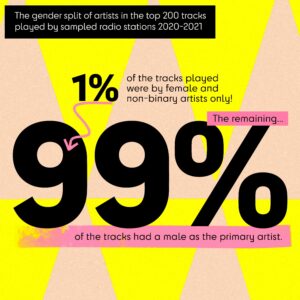

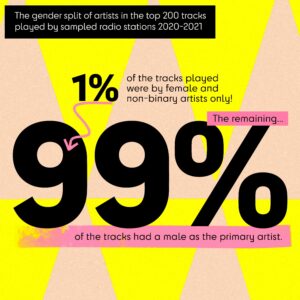

Women and gender expansive artists’ music is not playlisted by streaming platforms, is streamed less times than cis men’s and played much less on the radio. Cis men still dominate festival stages, and importantly, take a lot more of the top billed slots and main stages. This is made even more significant when we take into account the strong shift towards people now encountering electronic music at festivals rather than clubs – especially since the covid-19 pandemic. Women are also absent on event line-ups in clubs too, although the figures on this are very thin on the ground. In short, women and gender expansive artists are not visible as performers of electronic music in the places we listen and/or dance to it. They do not appear as producers signed to record label rosters, music store charts, and are a tiny proportion of the technical credits on electronic music tracks. This means women, trans and non-binary people don’t register themselves or their music for royalties and few use music publishers, which – along with the rest of the underground music production scene – is partly because they are freelance, part-time ‘bedroom producers’ not earning enough of an income to even consider themselves to be music producers.

But women and gender expansive artists are out there and the work of finding and platforming them is vital in deactivating the cloak that keeps them hidden – the myth that there are no women producers. Finding music by minoritized artists is essential in order to change perceptions that there aren’t any but it takes time and effort. And it is usually left to the very people who are marginalised to do it, for no pay and often no recognition while others take the glory. The identity tax effect is high and it’s part of the ‘ameliorative work’ that loads women, trans and non-binary people with more to do than their cis male counterparts, compounding their disadvantage and making the playing field even less level. It’s structural inequality.

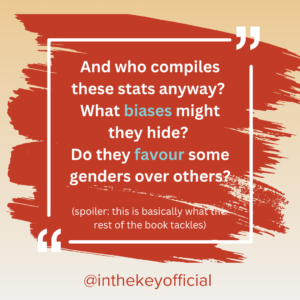

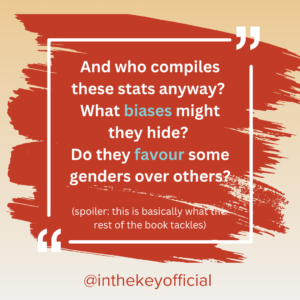

Structural inequality refers to the way resources are distributed in society in ways that favour one group over another, but are taken for granted as neutral and fair because people have forgotten their origins[i] In relation to gender. It is the way cultural and implicit biases, stereotypes, misogyny from (cis) men’s fear of women, habit, routine and downright mean-ness have become hard-wired into the operating systems of societies, which has the effect of erasing perceptions of discrimination because the systems are seen as fair. To uncover the bases for structural inequality then we need to question how a veil of ‘objective reality’ obscures inbuilt biases towards men and consider what fuels those social processes.

Applying this logic to the myth that there are no women producers, the question then becomes why aren’t women showing up across every measure we use? Where are the biases in our measures? Put simply, most of these measures involve some form of gatekeeping. They are not objective measures like the height of a tree or the temperature water boils at when at sea-level, they are the result of all manner of social processes. The top selling music and sell-out gigs that the available statistics are mostly compiled from do not happen by accident. Someone makes a decision who to book for an event, who to sign to their record label, what tracks to compile into a streaming playlist. As that person is highly likely to be a (white) cis man it’s also highly likely that (white) cis male interests will drive what talent looks and sounds like. So what we are most likely measuring are the outcomes of these social processes – particularly ones that are legitimated by economics. Almost all of the statistics mentioned above are driven by market forces – music sales, the selling of tickets to gigs and festivals, and the commercial return on maximising streaming income, for example. This is how success is defined, even if that’s less the case in the underground. Ultimately it is market forces that determine who gets seen and heard, who gets regarded as ‘the best’ and makes it into the top slots, rankings and award nominations – and crucially who does not. These statistics show us who gets chosen because their music sells and/or they are ‘marketable’. But that’s a very biased process.

Explaining what we can do about this is ultimately the aim of my book. A book that is based on six years of immersive research in the electronic music industry including learning to produce music myself, interviews with over sixty women producers, and a role at an industry professional body. I’ll be showing how the walls of structural inequality can be demolished by unsettling their foundations and taking a metaphorical sledgehammer to the various bricks that make them up, decloaking ameliorative work in the process. I know this is possible because the women I have been working alongside over the past six years are already doing it. It’s important to note here that whilst ameliorative work is indeed an additional burden, recognising women’s agency and their power to resist and subvert societies’ structures is essential to avoid positioning them as helpless victims. But it’s my contention that these sisters shouldn’t have to be doing this for, or by, themselves.

Resources listed in the Instagram swipe deck are:

Draw the Line Radio Show, Dynamics, In the Key Producer Directory, The F List For Music