Last month I was invited by the fabulous Natalia Data to take part in a ‘Women in DJ-ing’ panel at ‘SCWIM: South Coast Women in Music’ conference: a networking event put on by music degree students at Southampton Solent University. Being greeted with an excitable “Oh Hi! Are you the DJ from Cardiff?”, I was pretty sure the afternoon couldn’t get any better, but after (reluctantly) putting the organisers straight that I was actually the Professor from Cardiff researching DJs, I spent a fascinating few hours in the company of some amazing young women – fighting at the coal face of gender inequality for their music to be heard and their talents recognised.

This is the second post in a series I’m writing about women in electronic music performance and production and this time I’m writing about (in)visibility. It’s easy to think that there are simply less women in the scene than men as it’s hard to find, hear and book non-male artists for parties or buy their music. The most recent research on female participation in the music industry comes from the United States, and is on pop music. Between 2012 and 2017, 90.7% of Grammy nominations were by male. 16.8% of the top 600 songs in the U.S. were by female artists, only 12.3% were written by women, and (it gets worse) women made up only 2% of their producers. Published in January 2018 by U.S. Professor Stacy L. Smith and the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative who are campaigning for a more diverse entertainment industry, it makes for stark reading. But since my last post, I’ve jacked into a world of non-male DJs, and discovered a whole bunch of female collectives and initiatives, all deeply committed to supporting and normalizing women’s participation in electronic dance music scenes in the UK (and beyond). So maybe, as Corinne Przybyslawski begins her 2017 article in Mixmag:

Electronic music does not lack talented women. It lacks men who acknowledge their presence. Structural inequality within our industry casts an oppressive shadow over female visibility

Or maybe it’s just coincidence that everyone in music seems to be male. And why does any of this matter anyway? Good music is good music, right? So why does it matter who’s up there playing it, or who’s behind the scenes making it? Well, are you sitting comfortably? Then we shall begin.

Firstly, and perhaps most obviously there is the basic fact that our brilliant, musically talented girls and women have no role models. Can you imagine growing up believing you are excluded from the one thing that makes your heart soar and your sets your soul on fire? Never even considering that you could follow your passion for music just like the guys? At the time I was writing this, the awesome Eileen Lewis (kick-ass psytrance DJ, Khromata) happened to be posting on Facebook about the joy she felt being asked to teach a 9yr old girl to DJ – that is until the little girl dejectedly said “I’ll never be any good, because boys are better at DJing than girls…” I’ll let Eileen continue the story…

This little girl made the perfectly reasonable assumption that because she didn’t see any girl DJs in the world around her, they must be rubbish at it – what other reason could there be? The lack of visible women was also a theme generated by the ‘Women in Sound on Sound’ research at Lancaster University from women across wide age-ranges and backgrounds (more about this project in Part 3 of this series, coming soon) – being the only girl in a class of boys, never hearing of women in the history of music (let alone electronic music, or music tech) and not being taught by women. And so these foundational experiences cement into attitudes for later life. One of the delegates at the SCWIM conference embarking on a career in music marketing at 22 told me, “When I left school, I had no idea that music was even a thing you could do for a living, let alone something that I could do as a girl.”

Let’s take a closer look at the visibility of women in music performance. Wipe the male acts off any festival flyer and you get a real shock. Coincidence?

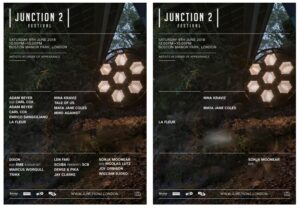

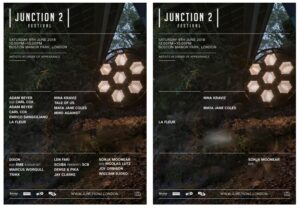

There are a few of these floating about the Internet, I’ve just picked Reading, Creamfields and Bestival from 2015 – Bestival clearly doing the most here to ensure greater female representation across their line-up. I found these posters so arresting when I saw them that I decided to bring them up to date and into techno/ tech-house scene I call my home. Here’s the flyer for Junction-2 festival I’ll be stomping at in June.

23 acts on the flyer on the left, take away the men = 4 women (flyer on the right) with Nina Kraviz and Maya Jane Coles being firmly in the world famous ‘Superstar’ DJ category. So with that in mind, lets dig underground a bit and see what’s happening at the grassroots of the mighty techno bushes and trees. As I was writing this (spring 2018), Whartone Records advertised the line-up for their Hidden Valley take over at Nozstock, a small friendly independent electronic music event in Herefordshire (UK). A pattern is emerging, no?

And then I took a deep breath and ran the line-up poster for Noisily through my top-secret magic gender equalizing machine. Noisily is my favourite electronic music festival, if not my favourite event of the year. I’ve been going since it started and consider it the finest collection of underground talent, showcased with incredible production, by a super-lovely bunch of guys. It also has the most creative artistic programme of any UK festival IMHO – big guns included. So. You can probably imagine my horror when I saw this.

Unless I’ve made a mistake, from 89 acts on the line-up, only 3 feature a woman. And one of those has a bloke in it (Slamboree Soundsystem). To give Noisily their due, I have seen Dani and Just Her play there, and I know there have been one or two female Psytrance acts too – but this is in seven years of programming. Earlier this year, the festival also posted a call for female DJ’s on their Facebook page – a welcome move indeed! – except the request was for artists to appear on the ‘side stages’, playing sets other than techno or trance. I still don’t know how to feel about this. “Come on in girls! But oh, could you just stand over in the corner please? There’s a love…” Other comments I heard from (male) friends were that this was just a cynical attempt to broaden appeal in the age of #metoo, but again, but I don’t know how I feel about that– I mean how on earth will the establishment change if we don’t start somewhere? But for now, the line-up speaks for itself.

Let’s take it down a stage further – this is a flyer for a little fund-raiser night in my hometown. You can’t get more grassroots than this. Surprise, surprise, 40 DJs. 39 men – and I’m only assuming Ms Mono is a woman as I can’t find anything out her/him in my Observers book of DJs. And we’d better not get started on the artwork or we’ll be here all day… but more about that in a later post.

What truly saddens me about all of the above, is that in all the years I have been raving and listening to various forms of dance music, it has never occurred to ME that almost all the acts are men. It has become entirely normal to me to see men everywhere in club and festival land and not think this is odd, because generally, we tend not to think too hard about the cultural forms we encounter as entertainment and so they seep in through our senses in an unremarkable way. It’s an incredibly powerful form of conditioning. Why are there so few women barging the men out of the way behind the decks and in the studios? A lifetime of seeing no-one like you in the public eye, on the stage, or the screen – with those you do see being there in scanty clothing looking pretty (a WHOLE other source of anxiety we can’t go into right now) – means you would have to transgress society’s powerful gender norms to even think about participating. At any age this does not feel nice. As a teenager it’s pretty much unthinkable. Grayson Perry’s wonderful book The Descent of Man, reminds us that

…when we are forced to become uncomfortably aware of our sex, race or class, it often signals bias in the system

If women are deterred from entering ‘the system’, and/or feel held back because they don’t feel it’s a place for them, it limits their life chances. This is sad enough as it is, but the economic costs are also high. According to research published in 2016 by Dr Linda O’Keefe of Lancaster University, 90% of students on electronic music production degrees at university are white males. Now, I’ve not explicitly mentioned anything about ethnic diversity or sexuality or other forms of inequality in these posts yet (although I’m very aware that the photo of the SCWIM organising team above is a very ‘white’ image), but the structures that deter women’s participation in the business are very likely to work against all forms of “difference”, because to quote Grayson Perry again, our culture is built on a yardstick of ‘normal’ as measured by what best serves the interests of “Default Man” – a category of people who are white, well off, well educated, conservative and above all male. He is at pains to point out it’s not just women who lose out under ‘Default Man’s’ operating system – its everyone who doesn’t fit. This was a theme picked up by ‘The Secret DJ’ in a Mixmag article recently – that DJs from privileged, wealthier backgrounds who will ‘pay to play’ are eroding the earning power of ordinary people who can’t afford such luxuries.

But back to gender for now, and why inequality matters. The UK has just seen the introduction of a statutory requirement for all firms employing 250 people or more to report how much they pay their male and female employees – the difference between these is known as the ‘gender pay gap’ and in the music industry this pans out at over 30% across the top players – Warner UK, Universal UK, and Sony UK (Maine 2008; Paine 2018). This shows that very little has changed in nearly a decade, when figures from a 2010 UK Music report reported that almost half (47%) of women working in the music industry earned less than £10,000 and only 6% brought home £30k or above. This is not because anyone actively pays women a lower wage than the men they work with – it’s to do with seniority, and the fact that there are way fewer women in the top, visible, higher earning roles than men. The same story as everywhere else in business, only worse.

So what’s the answer? I want to see more line-ups and flyers like these…

Two women on a line-up of six at the Boomtown warm-up, and a gender balanced double-bill below*. Breaths of fresh air! But how can we turn promoters away from ‘sausage-parties’ and towards a more inclusive, eclectic stage? Is it even the promoters we need to turn?

As part of my research I’ll be thinking more about this and in particular, women’s music collectives and groups. Do initiatives like all female line-ups really open everyone’s eyes to greater female visibility, or if there’s a danger they lead to further marginalisation of women in the scene?

*again, the artwork is interesting here, with the female artist behind the man, at his shoulder, but lets dwell on that later, huh?